Jointly creating

equitable societies

during conflicts

and in their aftermath

Jointly creating

equitable societies

during conflicts

and in their aftermath

The risks of a conflict resurgence after a peace agreement are high: approximately half of all countries emerging from civil wars experience armed clashes again within a decade after a peace treaty.

When women participate in the peace process, the likelihood of peace enduring even 15 years after the peace treaty is signed increases by 35 %.

Crises recur when the causes of the problems are not addressed. Establishing the rule of law, bringing about social justice and assisting in the transition to democratic societies are therefore important measures for preserving peace.

That’s why the Federal Foreign Office supports projects in these fields:

Laos

Gender equality in local mediation committees

Project partner

Association for Development of Women and Legal Education (ADWLE)

© ADWLE

In Laos, if a female farmer gets into a row with the ferryman on her way back to her village from the weekly market where she was selling chickens and fruit about whether she already paid for her return ticket, and the two of them cannot agree, they consult the village mediation committee. These committees are the first port of call in the Lao legal system and are responsible for civil disputes or complaints and smaller crimes which arise in village communities. The mediation committees are of great importance because their ruling determines whether cases or complaints can be brought to the court system.

Even though the committees are thus the first instance in the Lao legal system, their members receive hardly any formal training from the government. Some committees base their decisions on customary or traditional law, which can be very disadvantageous for women, rather than on national legislation, which prohibits gender-based discrimination. In addition, women are significantly underrepresented on the committees. This can lead to the row between the female farmer and the ferryman being judged unfairly and in a discriminatory way. In criminal cases concerning sexual violence it is also possible that committees misjudge the gravity of the offence and consider themselves responsible even though the cases should be referred to the criminal courts. This can lead to the trivialisation of sexual violence such as rape or the covering up of the offence.

The organisation Association for Development of Women and Legal Education (ADWLE) wants to bridge this gap. It is taking a two-pronged approach: in close cooperation with the responsible justice authority, the organisation offers gender-sensitive legal training for committee members in the Sangthong district in the Vientiane Capital region. The aim is to improve the training programme and raise awareness among the committee members of gender equality, children’s rights, women’s rights and human trafficking. In parallel the organisation carries out awareness-raising work in village communities and schools in order to educate the members of these communities about sexual and gender-based violence, family law, gender equality and access to justice.

Somalia

Reintegration into society of women from armed extremist groups

Project partner

International Organisation for Migration (IOM)

© IOM

Despite the progress which has now been achieved in stabilisation and state-building in Somalia, the situation remains precarious after decades of armed conflict, uncertainty, political instability, poverty, societal divisions, natural disasters and insufficient economic development. Violence remains a daily occurrence in many parts of the country.

Armed extremist groups further fuel the conflict and are the most direct threat to peaceful development in Somalia. Since 2015 Germany has supported the Somalian programme for dealing with former members of armed groups and at risk young people, which is being implemented with the help of the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and other partners.

The aim of the programme is to create viable, reliable, transparent and nationally accepted processes to enable exit strategies for former members of armed extremist groups and to support them with their reintegration into society. In this way the programme is reducing the drivers of conflict and encouraging resilience at individual and societal level.

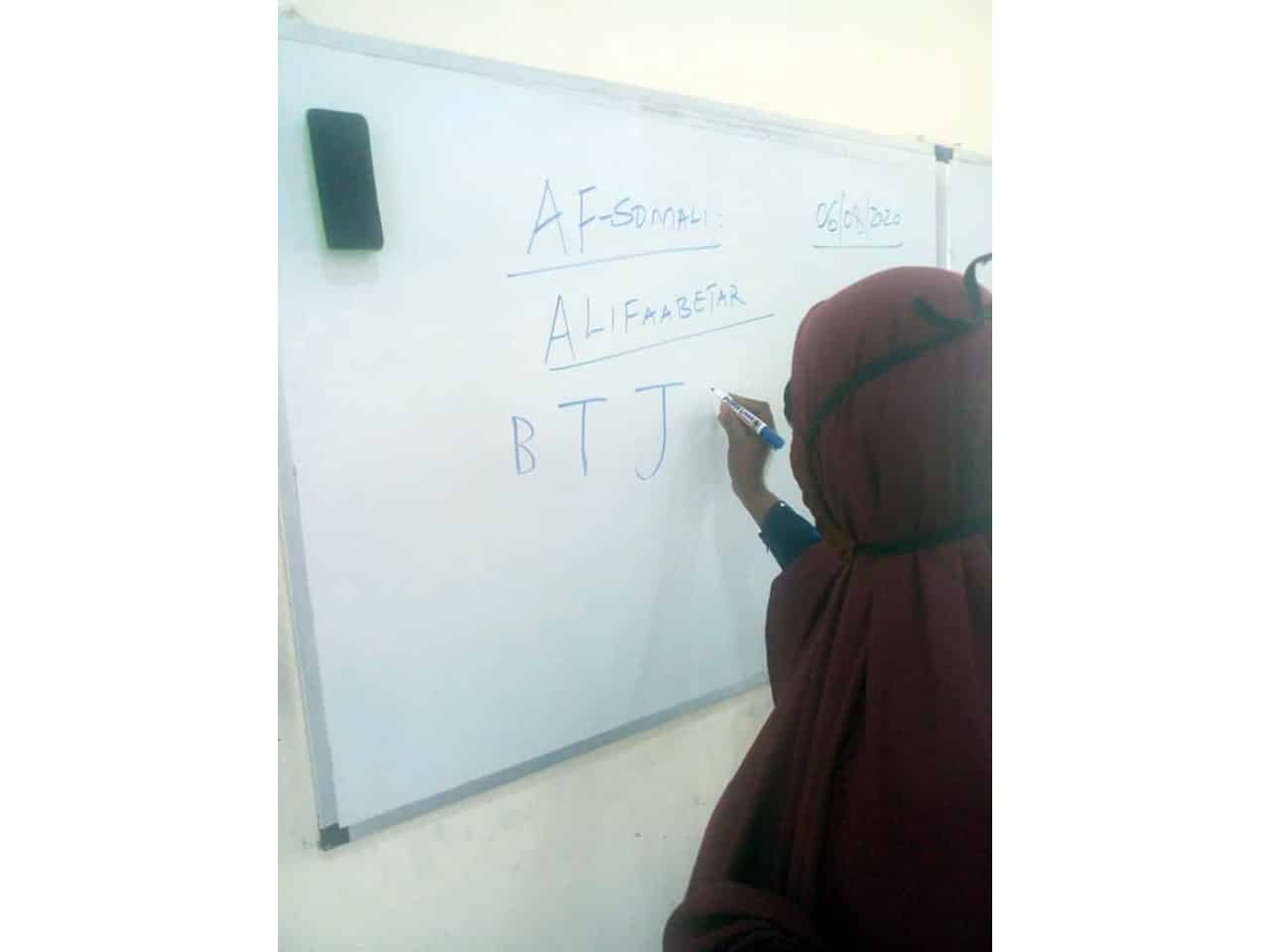

The programme also considers the particularly vulnerable situation of women and girls formerly associated with extremist groups who are often survivors of conflict-related sexual violence. Comprehensive and gender-specific rehabilitation and reintegration programmes are offered which support women in returning safely to their communities. In rehabilitation centres, individuals formerly associated with violent and extremist groups receive full support; including monthly allowances, religious guidance, basic education as well as assistance in generating income and setting up small businesses. Female survivors of conflict-related sexual violence also receive access to hygiene sets as well as medical treatment and psychosocial support. IOM runs two rehabilitation centres for women in Somalia and works with three women’s civil society organisations. In 2019 the programme supported 180 women with their reintegration into society in Mogadishu, Kismayo and Baidoa.

Somalia

Women and young girls find their voice with Radio Daljir

Project partner

Radio Daljir

© Radio Daljir

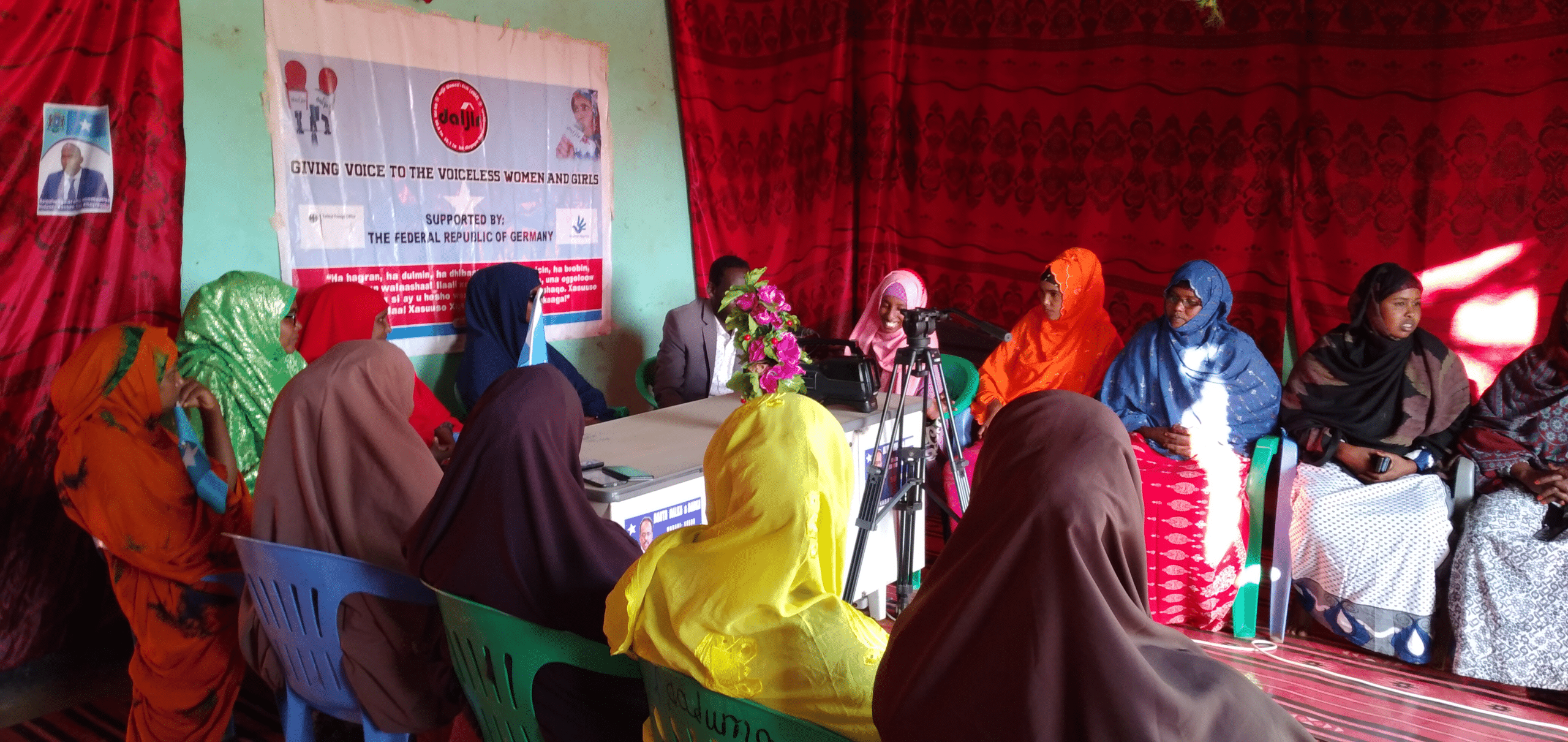

After decades of civil war the human rights situation in Somalia remains critical. The main triggers for human rights breaches are continuing armed conflicts in several parts of the country, including clan conflicts and the fight against terrorism. What’s more the radical Islamist terror militant group al-Shabaab continues to control areas in the south of the country and children and women in particular are suffering under its rule. State actors and other non-state actors are also responsible for human rights breaches. Sexual violence, forced recruitment of children as well as kidnappings, torture and illegal killings are widespread. Somalia is one of the countries with the world’s highest rates of female genital mutilation; the UN puts the percentage of affected women between the ages of 15 and 49 at around 98 percent. According to the UN, almost 50 percent of young women in Somalia were married before their 18th birthday. The percentage of women in parliament is 24 percent.

The local radio station Radio Daljir promotes regional development and human rights. It works together with human rights defenders and with local authorities. One main focus is the issue of gender equality: discussions, talk shows and radio plays highlight the themes of equality and equity between the sexes. There is a wide array of topics ranging from tackling and preventing sexual violence, the education and employment situation of women to the participation of women in political processes. Training programmes prepare young women to be Radio Daljir editors.

Between January 2019 and March 2020 and with support from Germany’s Federal Foreign Office, Radio Daljir was able to provide women and girls from Galmudug with the opportunity to exchange ideas about questions relating to gender equality in 40 radio shows, community meetings, training events and social media posts. At the same time this strengthened public awareness of these issues among the population.

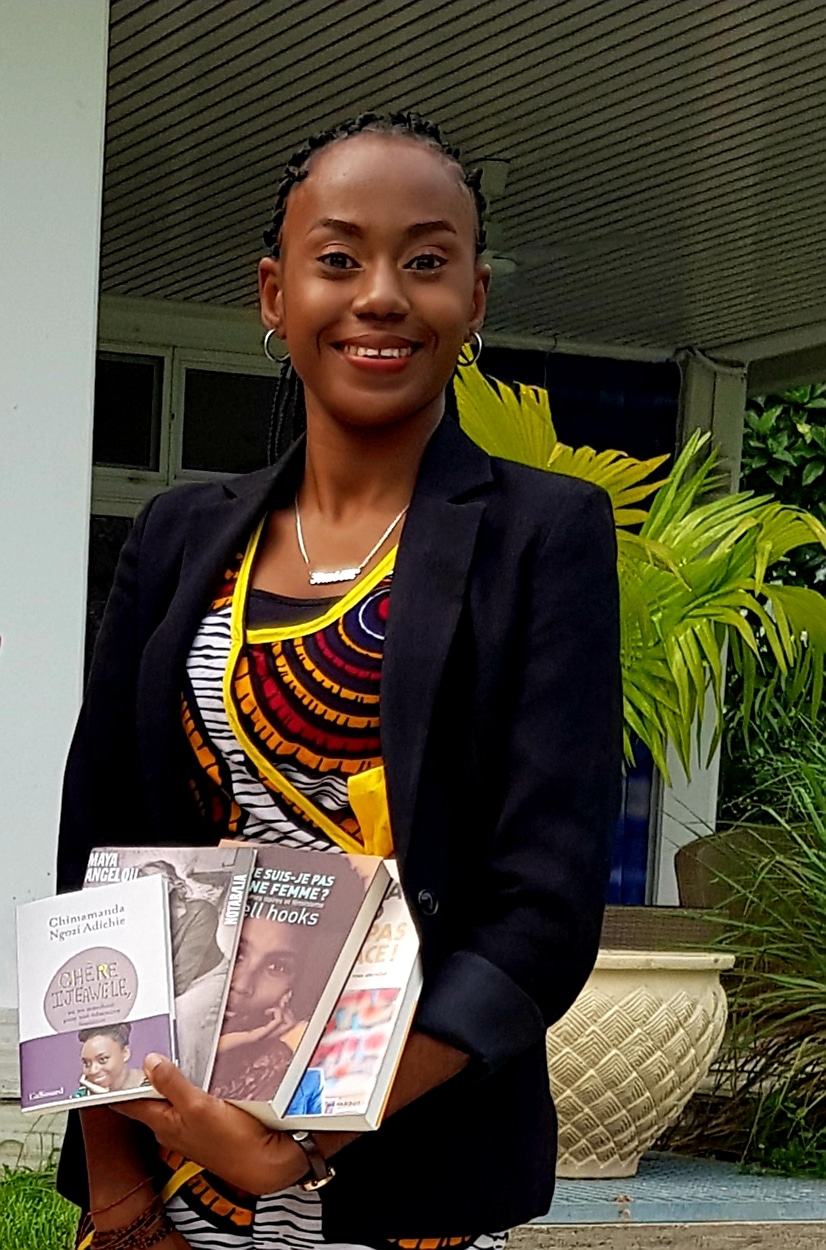

© German Embassy of Kinshasa

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Being a woman in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Women in the Democratic Republic of the Congo are fighting for equal distribution of power, equal rights and equal access to resources. The index of the United Nations Development Programme, which measures gender inequality, ranks the Democratic Republic of the Congo at 156 out of 189 countries. Particularly in the east of the country this also concerns involvement in conflict resolution and protection against sexual and gender-based violence, which has increased massively again in recent years and is destroying women, families and social cohesion across generations.

Yet the involvement of women in peace processes is more than a question of women’s rights: where women take part in peace processes, the agreements reached last for longer, are more strongly geared towards social change through political measures and more greatly involve civil society stakeholders. The inclusion of women in peace and security processes is therefore an essential element of such policies.

To mark the anniversary of Resolution 1325 on women, peace and security, the German Embassy in Kinshasa invited participants to submit their thoughts on the issue in the form of an essay, poem, short story or tribute.

Ruth Maketa impressed the jury with her poem “Being a woman in the Democratic Republic of the Congo” in which the medical student from Kinshasa addresses both the different roles played by women in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and those they will increasingly be targeting in the future.

Her winning poem was published in the French original on the website of the German Embassy:

Copyright: Jonas Wresch

Etre femme en RDC

Depuis que, des horizons du Congo

Le soleil, de l'aurore, a éclos

La vie de la femme congolaise

N'a ainsi cessée d'être une vie d'une fonceuse.

Meilleur cocktail de la création

La nature lui a doté d'un cœur en diamant

Et le soleil a peint sa robe d'une peau en mosaïque

Elle épouse les éclats de la lune

Et se substitue à l'ébène

C'est la femme-beauté

She gave her body to the Creator as a workshop

Où la création du peuple congolais a eu lieu

Elle l'a nourri de la sève de son cœur

Elle a gardé la flamme de sa vie afin qu'elle ne se meurt

C'est la femme-mère.

Cet être à tout faire

Celle qui fait fondre le fer

Celle qui cultive la terre

Celle qui, de ses larmes, éteint les terreurs

Sans jamais se plaindre

Et autant bénévole

plays all her roles

C'est la femme-au foyer

Réduite à la maternité, au plaisir sexuel

Restreinte à la lessive, aux casseroles

Elle se voit marginalisée, sans droit au mot

Jusqu'à ce jour par l'homme dans son désir macho

Elle reste dommage la femme-objet.

Rester bras croisés n'est pas son fort

D'elle dépend pour sa famille, survie et confort

Petit ou grand que ça soit son business

Elle y met abnégation et conscience

Ambition et détermination sont ses atouts

Rien ne l'arrête même la peur de son statut

She’s the businesswoman, the all-rounder.

Dans la détermination à diriger une entité

Elle se bat pour se faire une place dans la société

C'est la femme d'État

Celle qui se démarque, celle qui se bat.

Sans arriver à l'anéantir

Les coups de la vie font sa force

Entre deux cris, elle donne la vie

Entre deux larmes, elle transmet un sourire

Les coutumes ont cousu sa bouche

Mais par les battements de son cœur

Elle sait s'exprimer, elle est incoercible

C'est la femme invincible.

N'est ce pas là le meilleur cocktail de la création?

Pour un Congo encore plus fort parmi les nations

Let us value the Congolese woman

Elle est ce piédestal qui saura l'élever au rang des grands

Car la grandeur et elle font un.

Ruth Maketa

Being a woman in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Ever since the sun rose at daybreak

above the Congolese horizon

the life of the Congolese woman

has been that of a doer.

The optimum blend of creation,

nature gave her a diamond heart

and the sun coated her dress with a mosaic skin

She embraces the radiance of the moon

and supersedes the ebony.

She is woman and beauty.

She gave her body to the Creator as a workshop

to give birth to the Congolese nation

She fed it with the juice of her heart

protected the flame of its life lest it go out

She is woman and mother.

This being that does everything

that melts iron

that ploughs the fields

that wipes out fear with her tears

without even so much as a murmur

and with constant readiness

plays all her roles

She is woman and housewife.

Reduced to motherhood, sexual pleasure

tied to washing and stove

marginalised, denied the right to speak, to this day

by the man and his macho culture

Sadly she remains woman and object.

Doing nothing is not her strength

The family depends on her to survive

She goes about her business, whether large or small

with devotion and commitment

Ambition and resolve are her assets

Nothing holds her back, not even fear for her status

She’s the businesswoman, the all-rounder.

Determined to manage a unit

she fights her way up in the company

She’s the stateswoman

who stands out, who fights.

She’s not defeated by the hardships of life

Instead they make her strong

She gives life between two cries

She gives a smile between two tears

If customs have sealed her mouth

she speaks with the beat

of her heart, she is indefatigable

She is the unbeatable woman.

Is she not the optimum blend of creation?

For a stronger Congo amid the nations

Let us value the Congolese woman

She is the pillar upon which the country achieves great things

For greatness and she are one.

Ruth Maketa